House with a Sense of the Past

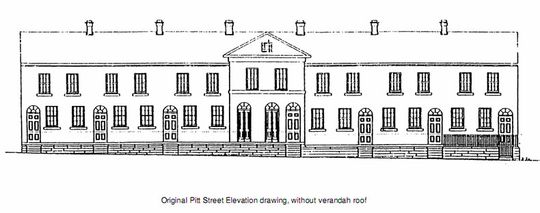

Dating back to 1845, Fitzroy Terrace is a Georgian-era row of seven terrace homes. Originally designed by renowned architect James Hume, Fitzroy Terrace is now considered a state heritage item. From Pitt Street, the terrace remains well preserved. From the rear, many of the terraces have undergone various levels of additions and extensions leaving a hodgepodge of lean-tos and outhouses at the rear of each terrace. What a contrast to the stern and ordered Georgian lines facing Pitt Street.

Rather than travel down the well-beaten track of demolishing the add ons to start with a clean slate, Welsh & Major Architects have worked with the exiting layers of history, creating a house that tells a story of its occupation for the past 170 years…

Contemporary Reconfiguration

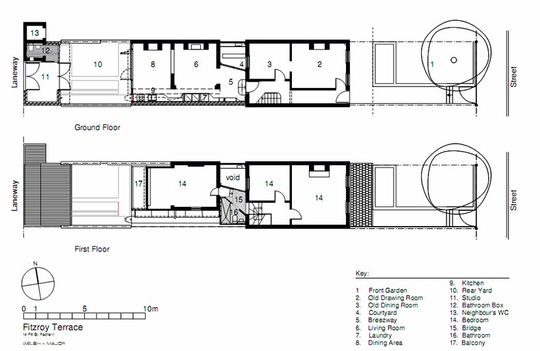

This particular terrace was in (possibly) the most original condition of the row. The owners spent a lot of time and money restoring the front two rooms — the drawing room and dining — to their original condition. So the brief of the project was to reconfigure the rear of the house to provide a contemporary kitchen, bathroom and everyday living areas as well as separate visitor accommodation.

Various Eras of Modifications

The architects had to deal with various eras of additions and reconfigurations to the original terrace:

- The original arrangement of the house consisted of the main front four rooms of the terrace, which were serviced by 2 separate buildings to the rear; a kitchen/scullery with a loft/store above and an outhouse.

- The kitchen/scullery had been linked to the main terrace sometime around 1890-1900, firstly by a single level laundry, then later by an upper level bridge.

- In the early-mid 20th Century the breezeway that existed between the two rear buildings was enclosed, leaving the rear lower room of the front part of the terrace isolated from natural light.

'Rule' Making

Rather than knocking the whole rear of the house down, the architects chose to use the existing fabric to form the basis of their new works. Their response was to develop a system of self-imposed 'codes' for dealing with the existing building and incorporating the new works:

- Use existing heights and ‘springing points’ to establish the rooflines of any new works. For example, the new studio roof uses the profile of the existing outhouse roof at the rear of the property which is then extruded to create a self-contained unit for visitors. Similarly, the upstairs roofline was used as the starting point for a new ‘butterfly’ roof which provides light and space for the bedroom.

- Materials used for new works can be found in other parts of the existing house. Preferably these materials are reclaimed from the site itself — bricks from the demolition were reused for garden walls and paving, timbers were reused as cladding. For example, you’ll find weatherboards on the ceiling of the dining area as well as the new rear facade.

- Salvaged timber is left unfinished; new timber is painted. Internal brickwork is simply sealed and left exposed. Original Ashlar render is left intact to indicate the extent of the original building.

- New wall openings are left with their brickwork exposed. Walls with existing openings are lined with new timber jambs.

- Replaced details such as balustrades, windows and thresholds use respectful, but clearly different adaptations of the originals.

Unifying the Layers of History

The use of these codes help to create a unified home that maintains the layers of aging and patina that makes older homes feel unique and full of character. The use of rules allows the modern interventions to wrap around the existing heritage fabric, making the new works feel less severe and allowing the history of the site to shine through.

Respect for the Past

Fitzroy Terrace has 170 years of history — admittedly not long compared to buildings in Asia and Europe, but significant by Australian standards. Rather than demolishing these layers of additions and extensions that have taken place over the years, Welsh and Major Architects have taken the unique (and brave) step of working with what they have.

The result, is a home that provides for modern living, without whitewashing what was there. The house is character-filled. Remnants of the past are everywhere — adding visual interest and character to the home. When you’re 170 years old, it just doesn’t make sense to try to look young again. Embrace those wrinkles!